Overview

In Light Source we took advantage of the a priori knowledge that our mesh was a sphere when it came time to compute our normal vectors. Now at the time that was a convient approximation to make, however it won’t always be an option. Moreover our mesh isn’t really a sphere, but a polygonal approximation to a sphere. In this article we’ll implement an algoithm to compute normals directly from the mesh data.

First let me clarify that there are actually 2 kinds of normals worth mentioning. Face normals are orthongal vectors to the faces of the mesh. Whereas vertex normals are orthongal to the vertices (what exactly that means will be discussed below). It turns out that in order to compute vertex normals we need the face normals, so we’ll discuss those first.

Face normals

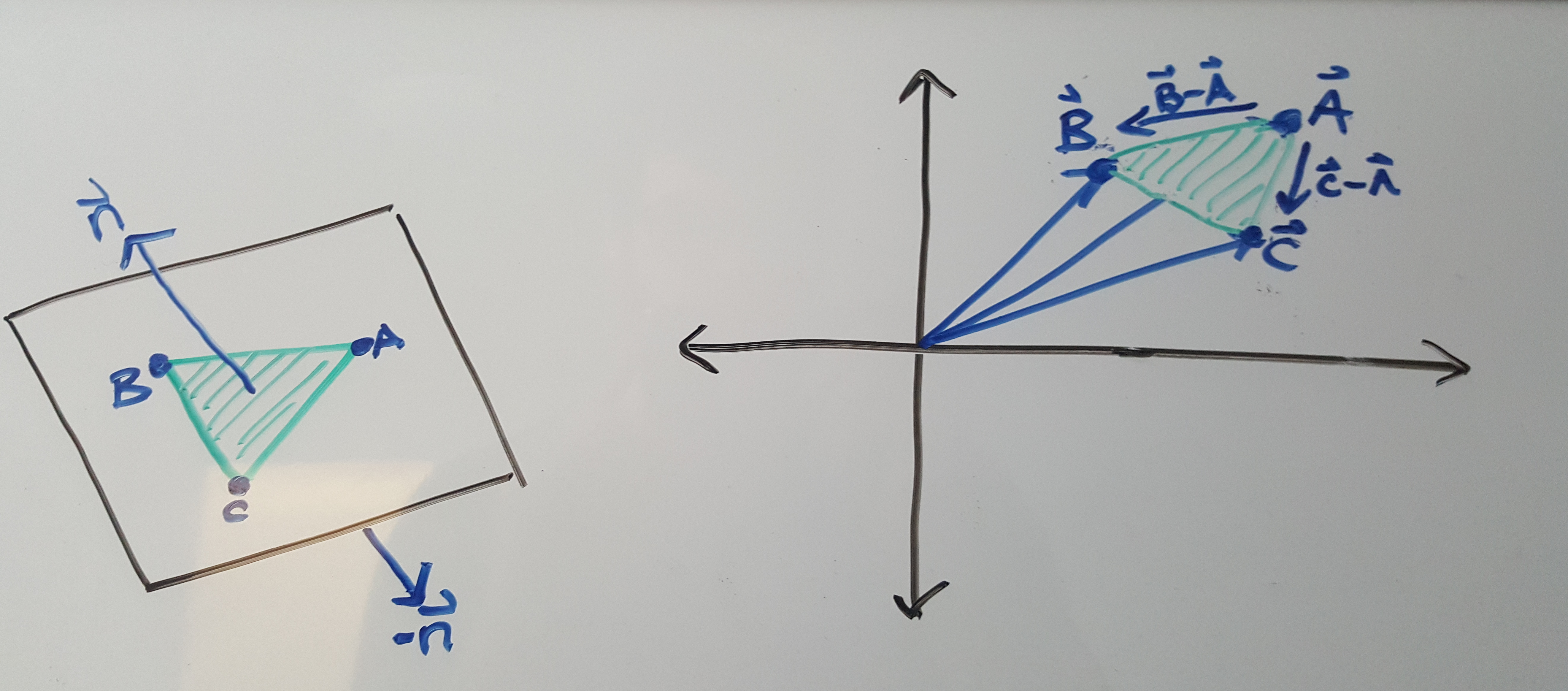

Since we are dealing with triangle meshes our goal will be to find a vector that is orthongal to the triangle face. Lets delve into that sentence. Triangles are typically represented as points, lets call them , , and . No matter the orientation of the points one can always define a 2D plane the triangle “lives” in. Or put another way, given a triangle you can always build a 2D plane from it. So when we say we want a vector that is orthongal to the face of the triangle, it is equivalent to saying it should be orthongal to the plane defined by the triangle. Now our question becomes, how do we compute the normal to a 2D plane? At this point is becomes easier to stop thinking geometrically and start thinking vectorially (did I just make up a word? Yes I did).

The points , , and can exist anywhere in 3D space, and as such can be represented as vectors , , , in . Any coordinate system will do, so we might as well use the one the mesh was defined in.

What does this change of mental perspective buy us? Well now we can make use of the cross product. The cross product is an operator that acts on a pair of vectors to produce a new vector that is mutually orthogonal to the pair. So, if we happen to have vectors that live in the plane defined by the triangle, the the cross product of those vectors would have no choice but to be othongal to the plane itself. (Take a moment to think about this and try to imagine a way to be simultaniously orthogonal to both vectors and not point straight out of the plane. It should become apparent that it’s impossible). Well it just so happens we have such vectors. The vectors and . There’s nothing special about the vector in this context, we could have chosen or to be on the right side of the minus sign. Armed with these 2 vectors our normal vector becomes

\[ \vec{n} = (\vec{B} - \vec{A}) \times (\vec{C} - \vec{A}) \]

There are 2 things worth noting about . The first is that it is not the unique orthongal vector to the plane. If is orthogonal than so is . We must be careful of this because we want our normals to be outward facing. That is, we want to embed the orientation of the triangle into the normal vector. Meaning the normal vector will determine the “front” of the triangle so to speak. If you find that your mesh is being lit strangely, or not being rendered at all, it’s most likely that you’ve inverted your normals accidently.

The second thing worth mentioning is that is not unit length. It’s length is proprtional to the area of the triangle. In most applications when we discuss normal vectors we assume that they have been normalized, since it only the direction we care about, not the length. However for what comes next it is useful to keep the length as is.

Vertex normals

Vertex normals are trickier to conceptualize but easier to compute than the face normals. If you imagine an isolated point in 3D space which direction would you say it is orthongal to? There is no correct answer because the question is ill-posed. Orthonality implies direction but a point has no direction assoicated with it. So how can we compute a vertex normal if that’s the case? If instead you imagine our lonely point as part of a surface then it becomes clear which direction the normal vector must point, away from . So if we have local information about the surface our point is sampled from than we can use that information to compute the normal vector at the point. Imagined in this manner the normal vector is a function of both the surface and the point on the surface you are looking at.

Once we discretize our surface into a polygonal mesh it becomes clear then that we need to make use of the surrounding vertices and faces in order to approximate . The easiest way to accomplish this is to average the face normals of the faces immediately surrounding the point. However an even better idea is a weighted sum, where faces with larger areas contribute more to the normal vector at the point. For a smoother varying approximation we could include faces further away from the point, but this also becomes less accurate as in the limit all the vertices have the same normal.

Model and Sphere

Naturally we will need to update Model to track both the face and vertex normals. We’ll be removing the normal matrix from the constructor of Sphere as we’ll be calculating them at runtime instead. You can find the code here and here.

Full algorithm

void Mesh::ComputeNormals()

{

int n_F = m_faces.rows();

int n_V = m_vertices.rows();

m_face_normals = List3df(n_F,3);

m_vertex_normals = List3df(n_V,3);

std::unordered_map<GLuint,Vector3Gf> vertex_normals;

for(int i=0; i < n_F; ++i)

{

GLuint a = m_faces(i,0);

GLuint b = m_faces(i,1);

GLuint c = m_faces(i,2);

Vector3Gf A = m_vertices.row(a);

Vector3Gf B = m_vertices.row(b);

Vector3Gf C = m_vertices.row(c);

Vector3Gf BA = B - A;

Vector3Gf CA = C - A;

Vector3Gf face_normal = BA.cross(CA);

if(vertex_normals.find(a) == vertex_normals.end())

{

vertex_normals[a] = face_normal;

}

else

{

vertex_normals[a] += face_normal;

}

if(vertex_normals.find(b) == vertex_normals.end())

{

vertex_normals[b] = face_normal;

}

else

{

vertex_normals[b] += face_normal;

}

if(vertex_normals.find(c) == vertex_normals.end())

{

vertex_normals[c] = face_normal;

}

else

{

vertex_normals[c] += face_normal;

}

face_normal.normalize();

m_face_normals.row(i) = face_normal.transpose();

}

for(auto iter = vertex_normals.begin(); iter != vertex_normals.end(); iter++)

{

Vector3Gf vertex_normal = iter->second;

vertex_normal.normalize();

m_vertex_normals.row(iter->first) = vertex_normal;

}

}

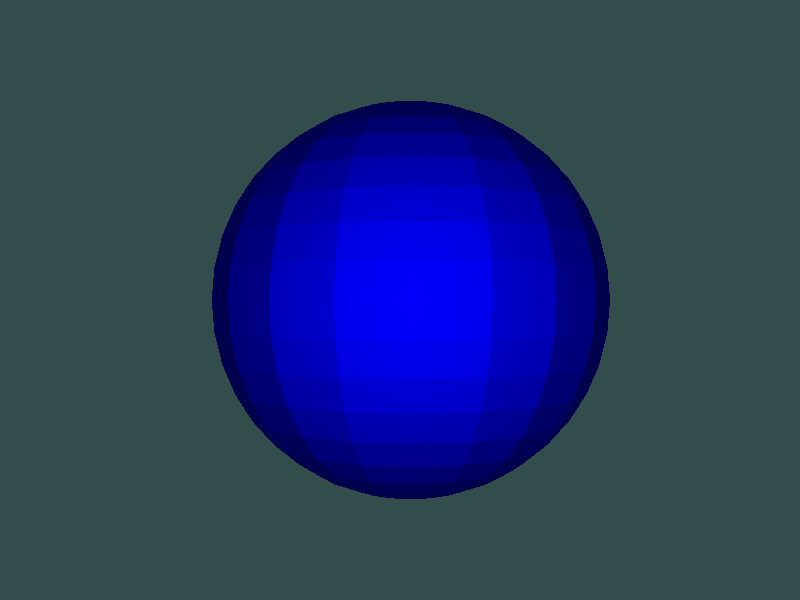

Results

Our sphere looks rather different doesn’t it? This is because of the way we build the sphere at runtime. If you’ll revisit the code you’ll notice that we recompute the same vertex multiple times but treat is as though it were a seperate entity.

As a result of this each vertex is in exactly face, meaning the vertex normals and the face normals are identical. I toyed around with the idea of rewriting the UVSphereMesh function so that it reuses vertices properly, but soon enough we’ll get around to implementing a proper model loading library. Then we can just grab a sphere mesh of the net.